Estimated difficulty: 💜💜💜🤍🤍

Chances are, if you study or work in Information Technology, or specifically the realm of Information Security, you’ve heard of security management. Security management, though broad, is pretty nuanced and encompasses every domain of security in one way or another – this post will cover at a high level what some areas of security management are, (we’ll look at these in more individual detail in later posts) and briefly what some of the problems are that organisations face with security management.

What is security management?

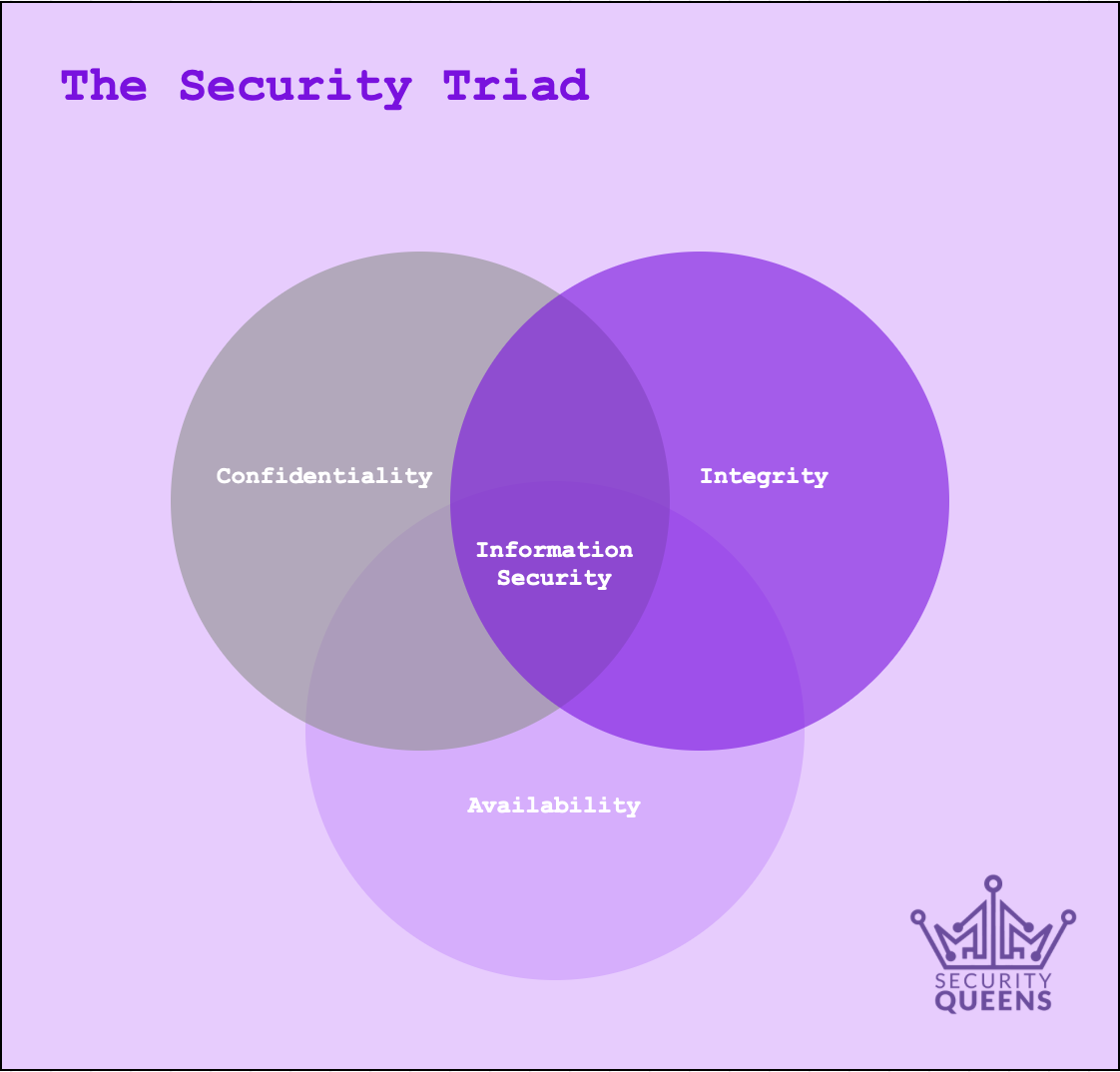

Information security management is the process of maintaining the confidentiality, integrity and availability of information assets and systems. Sounds pretty simple, right?

The tenet of confidentiality means that it shouldn’t be possible for an unauthorised party to access a system or view information. The concept of integrity implies the inability of unauthorised parties to alter, amend or manipulate systems or data. Availability means legitimate users and authorised parties should be able to access systems and information when needed.

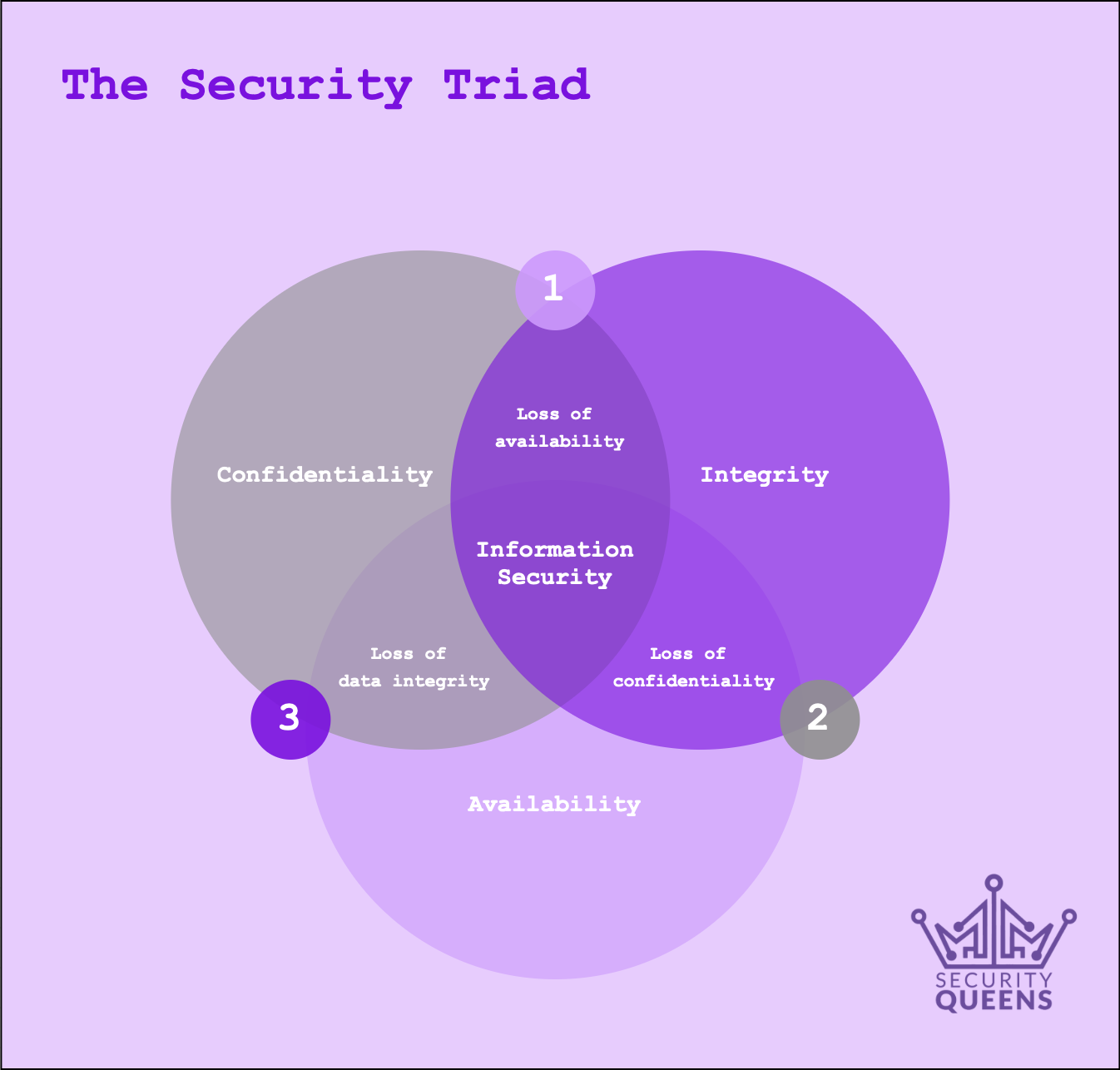

There are other principles associated with security (such as non-repudiation, the assurance that an action can’t be denied by a party at a later date – this appears in some threat models and can sometimes be provided using cryptographic primitives such as MACs); but these three core fundamentals are widely agreed upon and cover most bases. At the most fundamental level, in order for an information system to be considered secure, all three characteristics need to be maintained – the reasons being:

1 – If you have confidentiality and integrity, you can be assured that systems and data can’t be accessed or amended by unauthorised parties, but without availability there’s a risk of a denial of service against legitimate users (e.g. a service outage).

2 – If you have integrity and availability, you can be assured that information or systems can’t be tampered with or data altered by unauthorised parties, and that the service will be available upon legitimate request by authorised users – but without confidentiality there’s a risk of data disclosure (e.g. a breach).

3 – If you have confidentiality and availability but no integrity, the system and information is likely to be available for authorised users, and information kept private where required – but data could be manipulated or altered, and therefore become unreliable, or systems could be tampered with which could have an impact on availability or confidentiality.

There are quite a few sub-domains and disciplines of Information Security that influence the overall effectiveness of security management in an information system (an information system being people, processes and technology rather than just a computer network or the like). Some of these domains are listed below.

Domains:

Risk management

Risk management chiefly involves continuous oversight of the risk position of an organisation, assessment of emerging risks, identification of ineffective controls and shortcomings, and ultimately provides or influences risk treatment options and strategies (this might involve gaining investment or commitment from senior stakeholders to complete specific activities). These responsibilities can sit with a particular Risk Management function, a specific Information Security Risk team, or in other areas of the business depending on the size and makeup of the organisation, as well as the sector it operates in (some sectors are required by regulation to have named people who are responsible for anti-money laundering or data protection, for example). It’s important to note that activities such as risk assessment and identification of ineffective controls can take place across multiple areas of an organisation – sometimes these things might occur in what would traditionally have been considered a “first line team” (more on this below). Other key stakeholders in risk management include Executives and the Board, Directors, and senior leaders.

Governance

Governance is closely related to risk management, and may be carried out by the same or closely linked stakeholders, who will develop the Information Security Management Suite (ISMS – the documented security policies and controls to be operated and complied with). An ISMS is usually developed in line with existing information security standards such as the IEC/ISO27x series, CIS controls, and will be influenced by regulation and directives such as EUGDPR, PCI DSS and PSD2. Technical standards might be shaped by the NIST 800 series. There are a myriad of regulations, directives and standards in this space – but not all are created equal. Information security governance involves the development and operation of processes which support the implementation of the organisational security strategy. In other words, Information Security/Risk Management and Governance set the top-down approach and play a big part in the development of a security culture.

Compliance

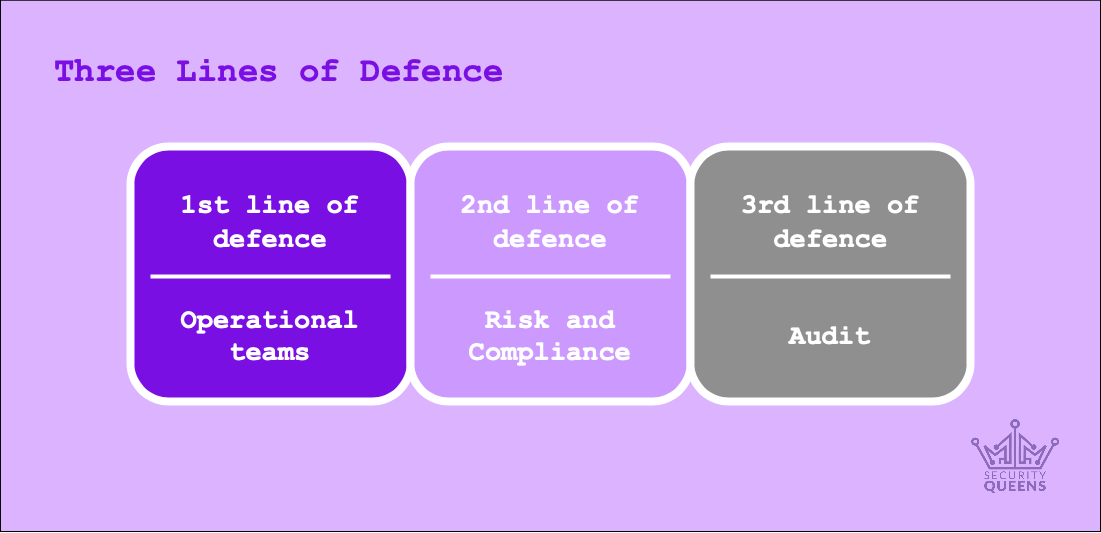

Compliance are responsible for ensuring that the policies, procedures and standards outlined by the governance and risk management teams are adhered to. Usually a compliance team will conduct an audit of an operational area to test the effectiveness of controls, and that processes are being followed and regulations complied with. There’s a degree of overlap between these teams, and in some organisations a few of these activities or responsibilities may be owned by the same teams. Compliance and risk teams are referred to as “second line” teams – this refers to the three lines of defence model of risk management, developed in the 1980s – outlined below. It’s important to note that compliance and security are absolutely not the same – an organisation may be compliant with a standard or a piece of regulation, and still have hidden vulnerabilities or an insecure technical estate. Compliance is a powerful tool that can assist security teams with establishing engagement and implementing controls to improve security posture.

Audit

The main function of an audit team (internal or external) is to provide independent (objective and impartial) assurance over the activity of first and second line functions and teams. An Internal Audit team for example, will usually report to the Board, and provides an evaluation of the effectiveness of security controls or risk countermeasures, and a level of oversight of the risk position of an organisation. Organisations in some sectors (i.e. finance) are required to be externally audited on an ongoing basis to verify the findings or position of Internal Audit, and Internal Audit departments are also audited to ensure they’re objective and effective. As a security professional, a good relationship with Internal Audit can assist you in gaining approval and investment from senior leaders to make improvements to your security controls.

Operations

Operations teams can consist of technical IT teams (e.g. Service Desk, Security Operations Centre, Access Control, Network Administration, End User Computing, and so on) or other teams in the business responsible for the operation of security controls. A good example of this might be in a contact centre, where customer service agents are responsible for verifying the identity of a customer before they can discuss account-specific details. Operational areas will usually be the team that “own” a risk – possibly arising from non-compliance with policy, or reliance on outdated technology (more on this below).

Incident management

Incident management is a business-wide discipline – in the event of a serious incident or a crisis, ordinarily a team will assemble consisting of nominated stakeholders from key business areas, to report issues, triage and investigate problems, and collaboratively make decisions to manage the situation as best as possible. There might also be a specialist technical Incident Management team in the IT department, for example, who lead the initial triage process, trigger the response of and feed information into the Serious/Business Incident Management team. A mature Incident Management team will have a series of playbooks to guide them through troubleshooting and ensuring business continuity (below). Remember that a Serious Incident Management team is likely to have Customer Service, and Internal or External Communications people involved, and interfaces with all areas of an organisation.

Second line – areas that provide some oversight and assurance of first line activity.

Third line – independent assurance of both first and second line activity.

Business continuity and disaster recovery

Business continuity and disaster recovery are technically different disciplines, but might sometimes be combined into the same function which manages overall operational resilience, or business continuity for a whole organisation. Business continuity, as suggested, refers to the ability of a business to continue to service customers or function as usual in the event of an incident, crisis, service interruption, etc. A good example of this would be the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic – some organisations were appropriately prepared to work remotely and had business continuity plans to be able to function relatively normally with a lightweight ~50% “skeleton staff” and so have been able to adjust pretty well. Disaster recovery then, concerns the ability of an organisation to recover from a critical hit – maybe a natural disaster preventing access to head office sites, or a ransomware attack. In these circumstances, there may be a failover data centre to prevent loss of services, or a secondary business site that employees can be re-deployed to if required. Again, the resiliency and scalability of cloud infrastructure can hugely assist with disaster recovery (if well-architected) and being prepared for close to 100% remote working enables you to cope with scenarios such as loss of sites.

Architecture and strategy

Architecture and strategy teams are responsible for change – they might engage with project teams implementing new systems, for example – and for visualising the overall strategy of an organisation, as well as the capabilities they want to develop and any regulations or directives that may require work to achieve compliance with. There might be a specific team or function responsible for security architecture, or there may be a more general architecture function that absorbs this activity.

People

Perhaps the most important part of the security posture of any organisation are the users. These are people outside of the security teams who work in other areas of the business – they’re the first line of defence an organisation has against external attacks in most cases. Think about phishing, social engineering, or the occasional piece of new malware that might get past an email gateway – and the ongoing awareness training that organisations do, encouraging members of staff to challenge unaccompanied visitors, or to be able to spot a phishing email and safely report it. Users are allies, and the way security management teams interact with them directly affects whether they develop a positive security culture – where users feel informed and empowered to challenge and report suspicious activity – or a negative security culture, where users feel disengaged or intimidated, or hide mistakes.

Common Security Management Issues

After considering the domains outlined above, a picture begins to emerge of how security management spans and encompasses an entire organisation – and it becomes easier to see how problems or weaknesses can appear in an overall security posture. There are common issues that occur as a result of failures in procedure or security controls, or issues that are inherently challenging to any organisation with a technical estate to maintain. These issues can be categorised in any number of ways, but briefly here are a few:

Asset and estate management

It’s pretty common for organisations to have designed their networks and in some cases to have implemented core customer service systems decades ago. These technical estates needed to scale considerably over this time due to organic growth of a business – rather than a full re-architecture of a network, components may have been bolted on, so the estate “evolved” into one that likely isn’t resilient (loss of availability of systems is a key risk here) and may be incredibly difficult to understand. Some organisations might not know what assets they’ve accumulated over the years, so plotting system dependencies and identifying operationally critical components can be challenging. Asset discovery and network mapping tools may provide some assistance with building a picture of an IT estate, but it’s easy to miss things depending on the architecture of the network and where the asset discovery tool is deployed.

“Technical debt” and “legacy IT“

These are key concepts to be aware of as a security professional. The idea that outdated and unsupported hardware, applications, protocols and so on are a “debt” isn’t new – and is a useful way to succinctly communicate that IT estates need continuous investment and support in order for security risks to be managed, and to provide the best technical customer service possible. “Why don’t they just upgrade/replace the old components?” I hear you ask. Think of this problem like a house (with people living in it), that needs to be re-plumbed in its entirety – but the people living in the house have nowhere else to stay in the meantime. Outdated or unsupported technology needs to be maintained because key systems or applications are dependent on this old infrastructure, so it’s difficult to upgrade or replace (particularly if the overall shape and state of the estate is unclear). There are some kinds of architecture (like leveraging cloud infrastructure) that can assist with the ongoing management of technical debt and legacy IT – really this is outsourcing the issue to a third party provider – but a migration to the cloud is challenging at the best of times, let alone with a potentially rickety understanding of an estate.

Poor access control practices

This point is sort of related to the previous two, in that a lot of legacy systems simply don’t have the capability to support long or complex passwords, or in rare cases, password changes. There may be shared administrative or service accounts due to a quirk in the initial implementation; hard-coded credentials, overly permissive access rules – this issue is both a hangover from the maintenance of systems that were developed without consideration for access control and security risk, and a modern philosophical issue about how to do access management properly. Processes may be implemented as a temporary workaround, e.g. test accounts set up with weak authentication to make life a little easier during the development phase of a project, and eventually it’s discovered that test accounts don’t comply with security policy password requirements, or an administrative service is single-factor authentication and uses the same credentials as a non-privileged account.

Vulnerability management and remediation

Vulnerability management relies on understanding the estate, the precise technical impact of a vulnerability or finding, and how this translates to a level of business risk. There may be resourcing or budgetary problems preventing the effective resolution of issues, or it may again be impacted by technical debt – e.g. vulnerabilities in unsupported versions of Windows Server that can no longer be patched. Vulnerability management is a pretty critical piece in terms of technical overall security posture, but it fundamentally depends on knowing what you own, and having the time, support and budget to fix things.

Software development lifecycle

One of the most widespread issues in the security space, affecting organisations of every type in every sector, is the introduction of poorly developed or insecure software. There are numerous reasons this might happen – because secure development practices aren’t in place or aren’t followed, new features are prioritised over security, vulnerabilities might be discovered in a particular library after the fact, and so on. One way to minimise this issue is to perform code reviews, security audits and penetration tests of new applications before introducing them to an estate – reporting any findings to the vendor to be remediated. In the future, this is something we might expect to see being more regulated, particularly for software being deployed in the healthcare and finance sectors, or that may support other critical national infrastructure.

This has been a very high-level, warp-speed introduction to information security management! There’s a lot more to say on this and it’s a vast subject – so we’ll be following this up with posts that examine some of these areas in more detail (like vulnerability management, and business continuity) – because they’re absolutely worthy of their own posts. As always, if you have any comments or questions, please leave a comment or get in touch via one of our socials. 😊

Thanks for reading!

Morgan x

tons of great info delivered in an accessible, thoughtful, concise manner. Thank you!

Thanks Beth – glad you found it useful!

What is security management in the realm of Information Technology and Information Security, and what are some of the key areas it encompasses? Additionally, what are some common challenges that organizations face with security management?